Dear Friends,

I’m sharing the New(ish) Books post of the week - in this case, including one not-new-at-all book.

Best,

Sam

CARL ERIK FISHER’s The Urge: Our History of Addiction (2022)

There’s a book I was hoping to read when I picked up The Urge. That book was something like a philosophical meditation on addiction: to addiction what The Myth of Sisyphus is to suicide. The thesis of it might be something like, addiction is the expression of our society. Whether it’s capitalism, stress, consumerism, we are all fundamentally addicts. That couldn’t be more clear seeing the way people are with their smart phones - and while there might be some disagreement about whether patterns of addiction are a reflection of our era or simply a deep truth about the human psyche cunningly crystallized by contemporary consumerism, what seemed clear was that more conventional addictions (drugs, alcohol) offered some orientation for the rest of us as we navigated the era of full-blown addiction.

The Urge is not that book. It’s at the same time more sweeping and more modest - a sort of encyclopedia of America’s grapplings with addiction combined with a harrowing account of the author’s own alcoholism, and all of it highly granular, highly resistant to any sweeping conclusions. If there is an overall thesis, it’s that “reductionist” approaches to addiction are never helpful, and that any approach to conceptualizing the problem (the ‘disease model’ or the ‘moral failings model’) inevitably reveals intrinsic shortcomings and gets replaced in yet another turn of fashion. This sort of attunement to complexity, this allergy to generalization, probably comes with the territory for any writer who has really studied a thorny topic closely, but it also makes for a frustrating book. It’s very easy to be overwhelmed by the welter of details in The Urge and not so simple to even say what I learned from it.

Basically, there have been so many turns of the wheel in the conceptualization and treatment of addiction that, one ends up concluding, everything has been tried before, everything is insufficient. Here’s some of what I learned in reading The Urge.

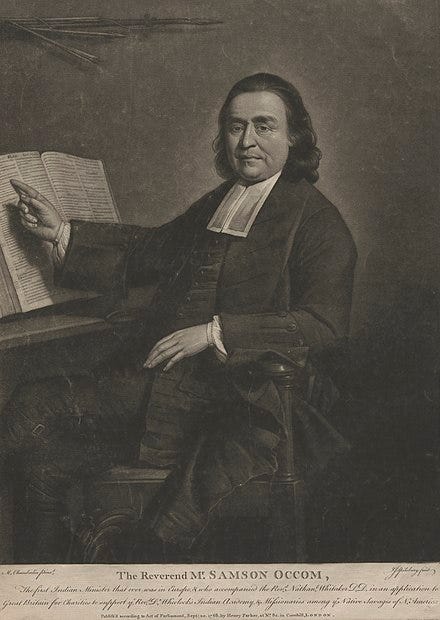

The first great temperance drive was initiated by a Mohegan preacher, Samson Occom, who in 1772 explicitly linked the epidemic of alocholism with exploitation, denouncing alcohol traders “who put their bottles to their neighbors’ mouths to make them drunk.”

The temperance movement was surprisingly late to come, even though Americans in the early republic were drinking alcohol at a truly gargantuan rate. Declaration of Independence signee Benjamin Rush struck the first blow for the ‘disease’ model by, in 1791, calling “habitual drunkenness a form of insanity.” But it was as if Rush “passed the torch from medicine to religion” and the ‘moral failing’ school took off when Lyman Beecher, in 1826, delivered his seminal sermons viewing alcoholism as a demonic entity requiring constant vigilance.

The AA model exists in surprisingly cogent form in the mid-19th century Washingtonians, an egalitarian group emphasizing fellowship and mutual uplift.

The Purdue Pharma pattern of pushing out a deeply unsafe product on the marketplace is nothing new - with both morphine and cocaine widely disseminated by the medical profession throughout the 19th century and addiction epidemics for a long time going unnoticed by doctors.

As with so much else in social relations, the 1880s emerge as a very dark decade in the conceptualization of addiction - with a more therapeutic approach to addiction generally abandoned and “prohibition on the march.”

The great impetus for drug prohibition actually comes from the American occupation of the Philippines, with the missionary bishop Charles Henry Brent pushing for a complete ban on opium and then helping to bring that sensibility to the mainland U.S.

The story of AA is a bit more muddled than I’d realized it was. The idea of alcoholism as a ‘disease’ isn’t particularly embedded in AA literature - Bill Wilson viewed it always as a “hybrid condition” - but the language of ‘disease’ spread under the charismatic influence of Marty Mann. Meanwhile, the ‘Minnesota Model’ of rehab advocating interventions and confrontation was a late arrival to AA - and was, to an unseemly degree, influenced by Synanon, the AA group-turned-cult.

Probably most interesting of all is the story of the ‘heretical data’ of the 1970s, with a series of studies indicating that there were effective alternative approaches to addiction other than the strictly abstinent AA model, and that addiction was often less of a one-way street than was frequently supposed.

This is sort of where Fisher lands - on the slightly more touchy-feely, fluid-treatment side of handling addictions. He inveighs at every chance he can against “reductionist narratives,” against “quick fixes and simplistic stories.” But, as in keeping for such a complex topic, even the case against reductionism is, in a weird way, a sort of reductionism. Part of the challenge with addiction is that it disrupts the normal functioning of the organism and sometimes, as is very clear, extreme solutions and ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches are the most effective means to wrangle with virtually untreatable addictions. Bill Wilson was captivated by a William James passage claiming that “the only radical remedy I know for dipsomania is religomania,” which is certainly an interesting thought - that, with extreme addictions, we move out of the normal band of secular psychology and only faith (if not fanaticism) is equal to the immense challenges of regaining and retaining sobriety.

And Fisher’s attempts to be utterly fair-minded and anti-reductionist can get absurd when it comes to heroin and cocaine. For him, much of the failures of anti-drug movements have to do with the reductionist divisions between ‘good drugs’ and ‘bad drugs’ and the facile moralism that, for instance, “drove negative stereotypes of heroin users.” But. Look. Either cocaine and heroin are dangerous substances or they’re not. It’s one thing to blame negative and often racist-based stereotypes for tough approaches to heroin and crack, but that’s not the end of the story. Heroin, coke, and crack clearly do disrupt the brain chemistry, and ruin the lives, of many, many users, and whatever the approach is to tackling their abuse, it’s really not sufficient to just blame ‘stereotypes’ and ‘reductionist’ mentalities.

I can certainly sympathize with Fisher’s difficulty in drawing any clear conclusions from the copious data that he presents to readers. In describing - movingly - his own alcoholism, Fisher writes of one very difficult moment in which he had to decide whether to accept an in-treatment program, “I talked myself in circles. I watched myself spin around and the spinning felt sick.” Fisher describes writing this book as being, in a sense, part of his continued recovery - an attempt to try to sort through the whirlwind of contradictory information about addiction and, more specifically, to find some breathing space for himself outside of the received pieties of the AA model.

In terms of any conclusion that I would draw, I guess I find myself somewhat aligned with Bill Wilson’s basic premises in the founding of AA. That it gets a bit silly to choose between the ‘disease’ or the ‘problem of the will’ premise, that addiction is a ‘hybrid’ condition, made up of ‘physical, mental, and spiritual’ elements, but that, paradoxically, a complex problem can admit of fairly straightforward solutions. In the case of AA, that was faith, abstinence, and fellowship. None of which is to say that there aren’t other approaches to reining in alcoholism, but that in designing a comprehensive program, simplicity and replicability are virtues.

What’s a bit missing from Fisher’s account are some of the utopian flights of fancy that Wilson and AA get into. The idea isn’t just that AA is fixing the specific problem of addiction. It’s that society itself is in a state of addiction, and that AA, like any religious community, offers a model for harmonious relations that can then be passed on even to those who don’t, narrowly speaking, have problems with alcohol or narcotics. As Fisher writes, somewhat begrudgingly, of his positive experience in the alcohol treatment center, “Like all the other best parts of rehab, it was nothing more than the experience of being around people who understood.”

In other words, all the medical jargon, and all the emphasis on best-fit solutions, are to some extent missing the point - which is to deal with addiction as an existential issue. The Buddha and St Augustine are mentioned briefly in The Urge - their point, the real basis of both Buddhism and Christianity, would be that everybody exists in a state of ‘craving,’ of ‘attachment,’ and that the path to better living lies precisely in this very deep battle with the root of craving. Baudelaire and Dostoevsky both treat modernity as, essentially, a kind of addiction writ large - the modern condition understood as compulsive behavior and with the form of the compulsion (whether gamboling, narcotics, or capitalist enterprise) understood as being sort of incidental to the underlying ‘urge.’ In any case, the iPhone makes this more than apparent. It becomes hard to talk about addiction either as a failure of the will or as a disease - it’s obvious enough that, in the context of a society-wide addiction, everybody becomes an addict - but the legacy of two centuries of temperance and AA are interesting to draw upon. Addiction itself but may not be a ‘failure of the will,’ but will turns out to be a very useful tool in the path towards health. The understanding is that the wonder drugs - Ozempic, methadone, and, before that, cocaine (!) - take you only so far. The real ‘work’ of addiction is a tough inner battle, a grappling with one’s inner demons and a drive to ask oneself: who do you really want to be?

PETER BROWN’s The Making of Late Antiquity (1993)

For no very clear reason, I’m going through a Roman history phase at the moment. I suspect the real reason is just that it’s fun and I didn’t know much of it before, but the smart-sounding reason would be that there are certain uncomfortable parallels to our own era in the decline of Roman civilization through the 3rd century CE.

What’s been on my mind is the sense that the slide from the Republic, and then from the rule of emperors in tandem with the Senate, to blatant autocracy is understood, in the context of that era, less as an aberration than as an inevitability. The politics of the 3rd century is a never-ending succession of palace coups, assassinations, mutinies by soldiers against their emperors, civil wars between claimants for the throne, and ending, finally, in the iron rule of a series of strong emperors, Aurelian, Diocletian, and Constantine. To any Roman of this period, it would have seemed obvious that republican rule was a mirage - a distant memory, deeply outmoded, and kept alive only through a corrupt and ineffectual Senate.

If modern American history is - in the ways that matter - a turn from a logic of a republic to a logic of empire, we seem to be at a particularly difficult moment. There was a genuine constitutional crisis in January, 2021 - the National Guard and the Capitol Police seemed less-than-nimble in protecting their elected legislators from a mob attack - and it took an intrinsic sense of civics by people like Mike Milley and Mike Pence to keep a very difficult situation from escalating further. Meanwhile, a certain optimistic myth about America’s role in the world seems, rapidly, to be crumbling - and, if American power internationally is none the worse for that, it stands more exposed as imperialism-for-its-own-sake, untethered to any soaring rhetoric about ‘freeing the world’ or ‘making the world safe for democracy.’

The 3rd century offers lessons in another sphere as well. What’s most arresting about it, from our vantage-point, is the sense of mentality shifting completely - of, as Peter Brown puts it, a transition from “one dominant lifestyle and forms of expression to another.” I’ve been a bit haunted, ever since I saw the before-and-after of Roman art of the 1st century and Roman art of the 4th century, with the sense that something went wrong - that the technically-masterful verist art of the Augustan period was replaced several centuries later by the rock-hewn slab of, say, the bust of Constantine. Of course, another era, looking at the art of the late 19th century as opposed to the art of the late 20th, might say the same about us - that at some spiritual level, we lost our grip, lost our basic grounding in reality, which, at first blush, doesn’t seem quite fair as a critique, but, then, again, may have something to it.

In a series of lectures in 1976 (published in book-form in 1993), Brown, who was for a long time the foremost scholar of this period, put together a much more sophisticated and granular understanding of the inner life of the 3rd century. For Brown, most of the ready-at-hand binaries - pagan v. Christian, rational v. superstitious, etc - are facile and fail to do justice to the dynamics of what was really happening in the very-dramatic period of transition. His overriding thesis is that the move from Augustus to Constantine wasn’t about becoming more religious or more otherworldly; in both systems, as Brown writes, “religion was taken absolutely for granted and belief in the supernatural occasioned far less excitement than we might at first sight suppose.” What shifted had to do with the dynamics of conceiving of divinity - with “divine power defined with increasing clarity as the opposite of all other forms of power.”

In the pagan model, divinity was fairly widespread and easygoing. Various communities - and, usually, the notables of communities, through time-honored means (temples, oracles, etc) - had access to the divine. In the period of transition, “a highly privileged area of human behavior and of human relations was demarcated....and Mediterraneans came to accept, in increasing numbers and with increasing enthusiasm, that this divine power was represented on earth by a limited number of human agents.”

Christianity, in Brown’s analysis, wasn’t some “disturbing visitation” from the outside of the classical world. It ran in parallel to major trends of the classical world of the period and was in many ways its most cogent exponent. As Brown writes, “Christians had a singularly articulate and radical contribution to make to that great debate on the manner in which supernatural power could be exercised in society.” Seen in that way, Constantine’s momentous conversion comes to seem less a radical departure from the pagan world than as the culmination of several centuries’ worth of cultural development towards a more transcendental and revelatory cast of mind.

The real issue for the classical world with an imposition like Christianity was, claims Brown, that ancient people had a somewhat modest relationship to the divine and an inbuilt suspicion of ‘sorcery’ or ‘demonism.’ There wasn’t so much a rejection of the supernatural in toto - the understanding was that sorcerers or demons were, in fact, in possession of supernatural powers - as a constant questioning about the appropriate applications of supernatural power. As Brown writes, “What was hotly debated was the difference between legitimate and illegitimate forms of supernatural power. This was a boundary which late antique pagans had learned to scan with alert eyes and firm criteria.” The initial difficulty with the claims of the Christians, just as with pagan holy men, was the sort of skepticism that made ‘Doubting Thomas’ have to verify the resurrection; or was, more broadly, a discomfort with the grandiloquence of the Christian view of the supernatural as opposed to the more domestic pagan equivalent.

The real work, in fusing pagan and Christian world views, seems to have been done in the realm of psychology, as opposed to theological doctrine. Brown is particularly fascinating on the ways in which ‘the supernatural’ becomes encoded in language of this period to evocatively describe what we might think of as ‘psychological’ problems. In the otherwise matter-of-fact divorce document of a fifth century couple, the collapse of a marriage is blamed on “a sinister and wicked demon which attacked us from whence we know not where, with a view to our being separated from each other” - which is as good a description of marital discord as any that the modern vocabulary has to offer. The Desert Fathers engaged in a series of extremely ascetic practices that - if the language were toned down slightly - sound a great deal like anger management: one monk went for three years with a stone in his mouth so that he would learn silence, another was discovered spitting out blood, which, he explained, was the physical incarnation of a cruel word spoken to him by a brother that he had in time digested and was now able to transmute to blood. The ‘guardian angel’ - or ‘higher self’ in the lexicon of contemporary spirituality - makes a decisive appearance around this time, “lodging contact with the divine in the structure of the personality itself,” as Brown writes.

Everything in Brown’s analysis feels right and helps to explain some of the deeply contradictory movements of this period. In the advent of the realpolitik of the 3rd century - which would seem to be a contrary impulse to the shift towards transcendentalism - Brown nonetheless spots a parallel. Civic relations of the 2nd century Antonines, he writes, were built on ‘philotimia,’ an idea of honor or ‘sheer willingness,’ in which citizens of distinction outdid each other in contributing to the commonweal. With the 3rd century, “the ‘sheer willingness’ of philotimia came to wear a more unpleasant face” - the careful balances of elites, a bit like the orchestrated pagan rites, giving way to a new sense of ambition, a desire not just to outshine, but actually to defeat, one other. In politics, a style of greater clarity - “blunt certainty” - emerges. “Diocletian and his advisors appear to have had no hesitation in calling a spade a spade,” Brown writes of the new imperial style that was ascendant by the period’s end.

And if, in Brown’s view, all the many movements of the 3rd century were, in a way, of a piece - the turn towards autocracy and brute force in politics, the acceptance of new doctrines of transcendentalism in religion, the growing ineluctability of Christianity - he is able to explain as well the ongoing pagan resistance to Christianity, which took the form, interestingly, of “deep religious anger” both in anti-Christian persecutions and then in pagan revivals after Christianity was firmly established.

The pagan objection really had to do with the Christian disparagement of the worldly, the sense that the salvational and transcendental doctrines of Christianity undermined the civic order. The beauty of the pagan system - the interflow between nature and society - was that pagan rites allowed practitioners to “draw upon an ever present reservoir of power, blessing, and inspiration….with the easy-going unity of heaven and earth mirroring the unity and solidarity of the civilization they had inherited.” The advent of Christianity, whatever its virtues and whatever its claim to divinity, meant abandoning that symbiosis. Brown gives the last word of his manuscript to Iamblichus, a pagan philosopher of the period, who wrote forlornly of Christianity, “This doctrine spells the ruin of all holy ritual and all communion between gods and men. For it amounts to saying: the divine is at a distance from the earth and cannot mingle with men, that this lower region is a desert, without gods.”

It’s a sorrowful elegy for the classical world in the face of Christianity’s ineluctable advance, but it becomes clear how different the classical world really was from our own. The point isn’t a turn from ‘secularism’ to ‘faith.’ The point, actually, is that the world - ‘naturalistically’ conceived of - is full of divinity of all sorts. Transcendentalism - which may be unavoidable in an era of stress and decadence - means, more than anything else, a turning-away from the world-as-it-is, and, with that, a certain contempt for reality.

Complex topics for sure. Sounds like an interesting book. Addiction has been so ruthlessly dissected at this point. There’s a big anti-AA movement going on and I understand what underpins it but I think there’re some fundamental misunderstandings around the big book/12-step model versus the actual complex culture of AA.

I wrote about this: https://michaelmohr.substack.com/p/misunderstanding-alcoholics-anonymous

With regard to Brown’s book, I recommend that people read the beginning of St Augustine’s Complete Works. This is a primary source for the period. The stuff about pagans and Roman behavior is not to be emulated and much stronger stuff than one finds in the secondary history accounts. As a writer, I find Augustine’s style (or maybe the translator’s style) interesting.